Slicing ISS budget

NASA scrambles to cut ISS activity due to budget issues

"The Budget reduces the space station’s crew size and onboard research."

Eric Berger

–

Updated May 7, 2025 6:50 pm

|

62

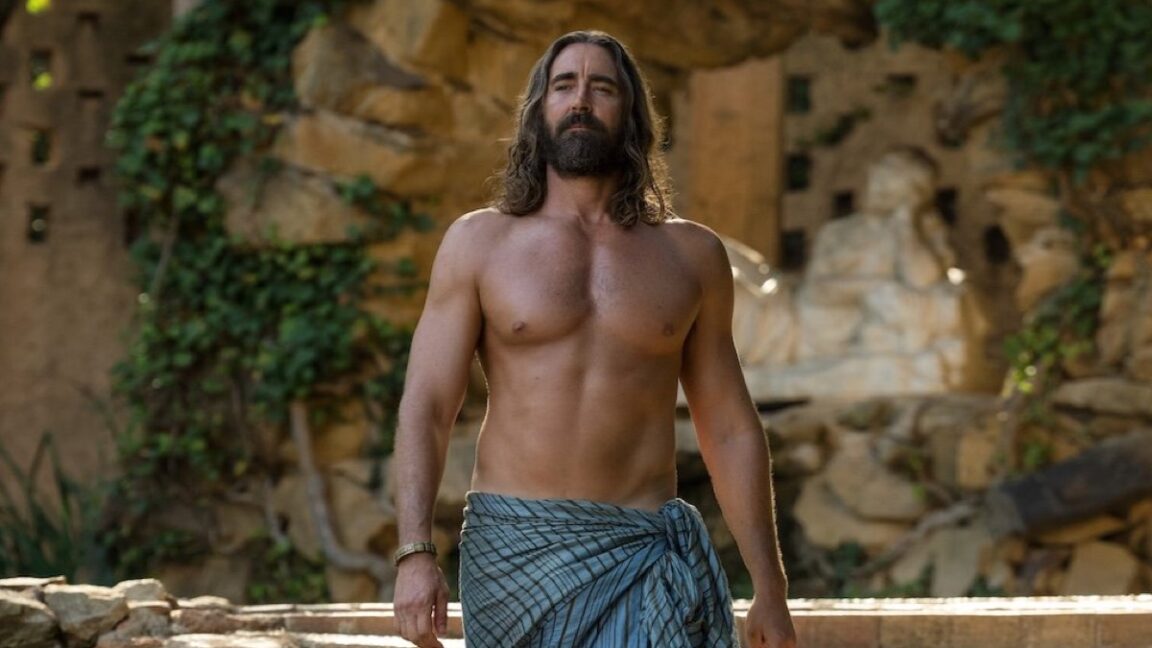

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer was installed on the International Space Station in 2011.

Credit:

NASA

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer was installed on the International Space Station in 2011.

Credit:

NASA

Text

settings

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Learn more

Minimize to nav

NASA is considering scaling back its activities on the International Space Station, according to multiple sources. The changes, which are being considered primarily due to shortfalls in the space station budget, include:

Reducing the size of the crew complement of Crew Dragon missions from four to three, starting with Crew-12 in February 2026

Extending the duration of space station missions from six to eight months

Canceling all upgrades to the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer science instrument attached to the station

The changes align with a desire that was reflected in the Trump administration's "skinny budget" proposal for NASA, released last Friday, which seeks to have the US space agency reduce its activities on the ISS.

"The Budget reduces the space station’s crew size and onboard research, preparing for a safe decommissioning of the station by 2030 and replacement by commercial space stations," stated the budget request for fiscal year 2026. "Crew and cargo flights to the station would be significantly reduced. The station’s reduced research capacity would be focused on efforts critical to the Moon and Mars exploration programs."

The president's budget proposal estimates this would save $508 million from a budget of about $3 billion annually to support the ISS.

However, Ars understands that the changes contemplated above were being implemented before the president's budget was released.

Nothing is final yet

Some of the changes contemplated here are not completely unreasonable. By extending the standard crewed mission from six to eight months, NASA would only need to fly three crewed missions to the station on Crew Dragon every two years instead of four. This would save a considerable amount of money in transportation costs.

Such a change would also match what Roscosmos plans to do with its Soyuz missions. Similarly, as a cost-saving measure and beginning with the Soyuz MS-27 mission launched last month, Russia has extended the duration of flights to eight months. The primary downside of extending missions for NASA is that fewer of its astronauts would get experience in orbit.

Canceling the tracker layer upgrade to the spectrometer would also not be catastrophic. The addition of a silicon tracker layer on top of the detector would increase the amount of data from the $2 billion physics experiment over the next five years by a factor of three. However, the experiment has been in operation since 2011, so it has had ample time to collect information about dark matter and other fundamental physics in the universe.

Cutting crews down to size

The real eye-catching proposal in NASA's options is reducing the crew size from four to three.

Typically, Crew Dragon missions carry two NASA astronauts, one Roscosmos cosmonaut, and an international partner astronaut. Therefore, although it appears that NASA would only be cutting its crew size by 25 percent, in reality, it would be cutting the number of NASA astronauts on Crew Dragon missions by 50 percent. Overall, this would lead to an approximately one-third decline in science conducted by the space station. (This is because there are usually three NASA astronauts on station: two from Dragon and one on each Soyuz flight.)

It's difficult to see how this would result in enormous cost savings. Yes, NASA would need to send marginally fewer cargo missions to keep fewer astronauts supplied. And there would be some reduction in training costs. But it seems kind of nuts to spend decades and more than $100 billion building an orbital laboratory, putting all of this effort into developing commercial vehicles to supply the station and enlarge its crew, establishing a rigorous training program to ensure maximum science is done and then to say, 'Well, actually we don't want to use it.'

NASA has not publicly announced the astronauts who will fly on Crew-12 next year, but according to sources, it has already assigned veteran astronaut Jessica Meir and newcomer Jack Hathaway, a former US Navy fighter pilot who joined NASA's astronaut corps in 2021. If these changes go through, presumably one of these two would be removed from the mission.

Will this actually happen?

The cuts are by no means a certainty. There was some confusion on Wednesday because, although the cuts appear to align with the Trump administration's goals, they were not being considered at the request of Trump space officials or in response to the budget release. Rather, they were made at the programmatic level.

This is because of a shortfall in the space station budget. According to one source, this is because the program used funding earmarked for other activities to begin funding a deorbit vehicle that would manage the safe disposal of the ISS at the end of 2030. Because of this, cuts are needed in space station operations.

None of these decisions are final, and may reflect the fact that NASA at present is operating under an acting administrator. The decision to fly fewer than a full complement of astronauts is not consistent, for example, with the goals of the Trump White House nominee to lead NASA, Jared Isaacman.

He spoke in favor of "maximizing" science on the space station during his confirmation hearing last month. In subsequent answers to written questions, Isaacman reaffirmed this position.

"My priority would be to maximize the remaining value of the ISS before it is decommissioned," Isaacman wrote. "We must prioritize the highest-potential science and research that can be conducted on the station—and do everything possible to 'crack the code' on an on orbit economy."

Congress has been broadly supportive of the space station, which is slated to fly through 2030 before being decommissioned. A final vote on the floor of the US Senate to confirm Isaacman could come within the next week or two.

The story has been updated to reflect additional reporting.

Eric Berger

Senior Space Editor

Eric Berger

Senior Space Editor

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

62 Comments